Almost a decade has passed since trend forecasters foretold the death of the conventional retail store.

In some arenas, their predictions of mobile commerce and on-demand logistics have come true. Online and in urban places, platform businesses are nipping at the heels of slower-moving brands with e-commerce and new kinds of physical experiences. Larger companies are pinning their hopes on “omnichannel” retail, which combines high-budget environments and integrated tech for seamless sales, logistics, and customer service.1

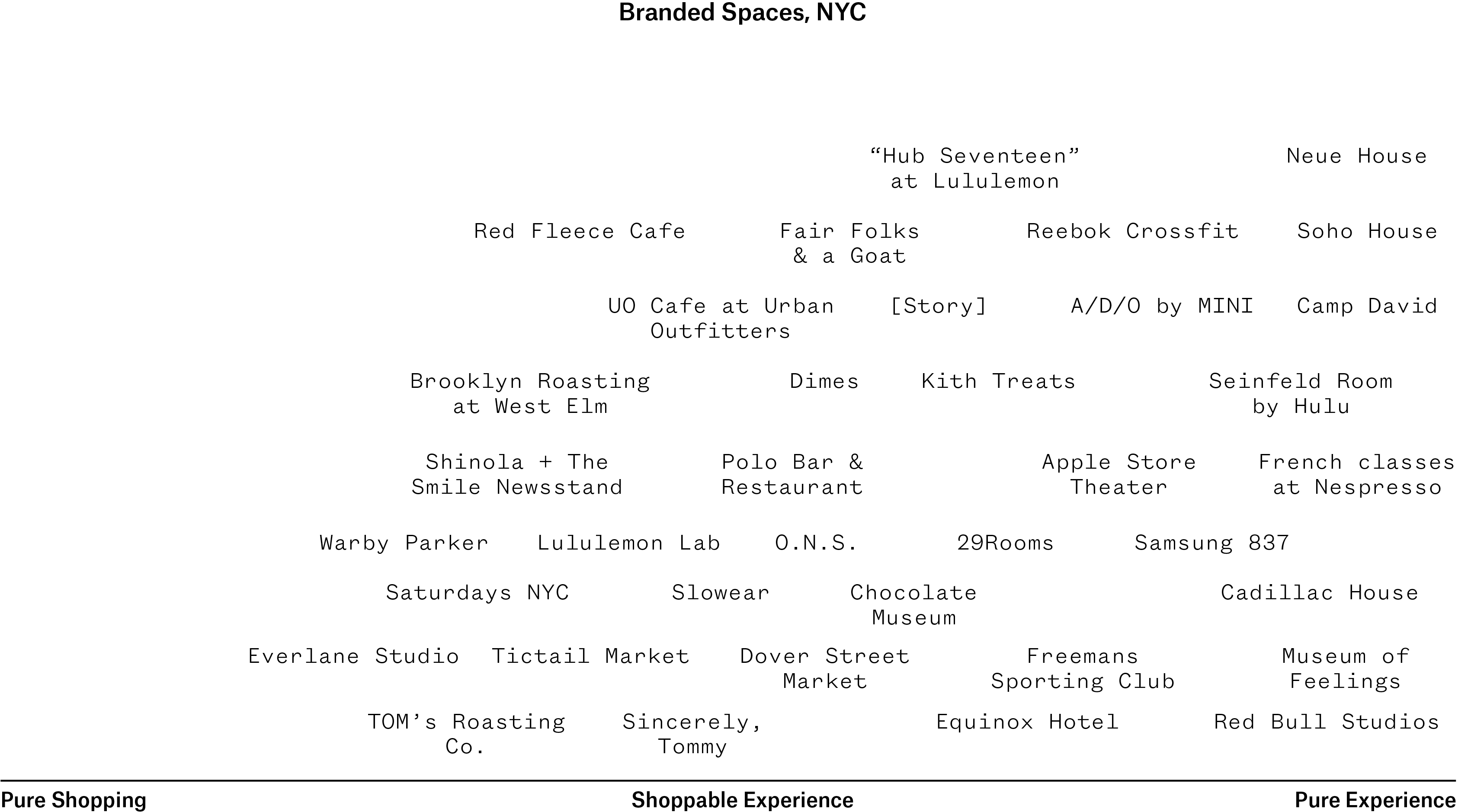

But even as transactions themselves are increasingly sublimated, the value of branded architectural space remains high.2 This is especially true in dense, affluent cities, where retail strategy is moving up the sales funnel: with less need for a literal point of sale, stores are transforming into branded environments more broadly construed as experiential marketing tools.

On its face, this kind of inside baseball about “future of retail” hardly seems relevant to deeper questions of urbanism. But branded spaces have looming implications for almost everyone that uses the city.

In a place like New York City, residential and public space are both so scarce that residents habitually “rent” social time at bars, cafes, and cultural institutions. Shopping, which became a quintessential American pastime under the advent of postwar culture and planning, remains a dominant way of using the city. But as purchases come to depend less on in-person transactions, brands are pivoting towards driving sales through aspirational experiences where the store becomes a more flexible backdrop for performing identity.3

New strategies for branded space necessarily harness real estate, consumer spending, and cultural production to the mechanics of social media platforms. It’s worth thinking critically about these processes in order to better approach how both brands and people are renegotiating a public sphere — one that is reproduced by audiences more and more fluidly distributed between offline and online “spaces.”

New Shopping

The current conventional wisdom on retail holds that digital sales cannot reach far enough on their own to build sustainable customer bases, so digital-first brands have migrated toward physical stores, pop-up shops, and other experiential marketing strategies.

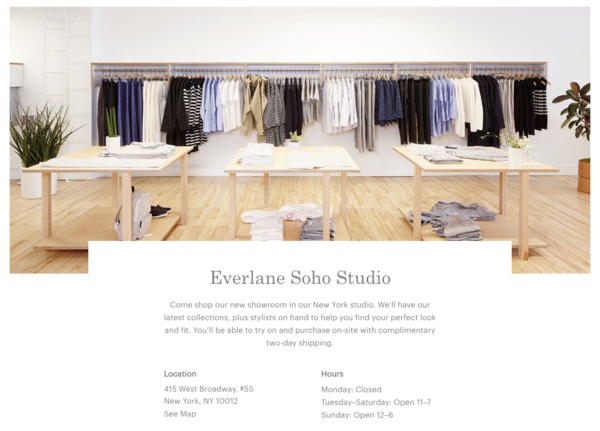

Clothing and accessories brands like Warby Parker, Bonobos, and Everlane are typical “post-digital” brands in this respect, building physical spaces around their e-commerce models in order to reach offline customers.4 These spaces are notable for reflecting branding lessons learned on social media onto real life and then back again. The blond wood and succulents at Everlane “Studios,” and the nerd-cool design details at Warby Parker stores, not only mirror the brands’ Instagram feeds but can be photographed and transfigured back into digital content with the exact same texture.5,6

The new branded space doesn’t merely satisfy a customer preference for finding products IRL. It opens up a new inflection in retail’s historical role as a venue for urban sociality, spectacle, and leisure. Just as the fin-du-siècle department store and the mid-century shopping mall thoroughly transformed the social worlds that produced them, the mixed reality experience of new branded spaces is reinscribing social behavior across the urban sphere.7

Everlane’s Shoe Park pop-up in SoHo was reportedly inspired by the flora of London’s Barbican Centre.

Everlane’s Shoe Park pop-up in SoHo was reportedly inspired by the flora of London’s Barbican Centre.

Think of the “Museum of Feelings” put on by Glade at Manhattan’s Brookfield Place in 2015, which mobilized the viral logic of experiential art projects like the “Rain Room” or Yayoi Kusama’s “Infinity Mirrors” to huge success. Or the stores, from indie labels like Saturdays Surf to corporate labels including Shinola, Brooks Brothers, and West Elm, that have carved out lifestyle spaces selling artisanal coffee and matte-finish design magazines.8,9

These post-digital branded spaces are designed to appeal to consumers whose relationships with physical experiences and with other people are thoroughly mediated by digital content. Content has become social currency, and it can only be mined through aspirational offline experiences. So what used to be a store has become an environment where social-mediagenic moments are easily staged and packaged for ongoing campaigns of personal branding.

The crisis facing both post-digital brands and people in this environment, which plenty of commentators have explored over the past few years, is the disappearance of authenticity in such an ecosystem. What happens when everyone is hunting for unique markers of personality and taste while simultaneously emulating widely popular and algorithmically curated patterns of behavior?10

Consumers craving “authentic” experiences tend to build their digital personas by recycling the same kinds of content that populate their own feeds. Especially on Instagram, photos of under-the-radar coffee shops, building interiors, and artful design objects begin to look utterly banal as they aggregate by the thousand. The real world, without any impetus other than the encouragement of the market, has conformed to these aesthetic standards in response.11

Brands build interconnected spatial and content strategies on top of these trends, reproducing a new visual and spatial landscape that appeals to the broadest version of their affluent, mobile-savvy target audience. Their reward comes in the form of mass “user-generated content.” Just as the mall once constituted a kind of forum for signaling identity, post-digital retail environments offer social media natives a set of commoditized visual tokens that tie digital communities to branded experiences.

Incubating Value

Not all new spatial marketing strategies emerge from the world of retail. For other businesses, especially those that don’t sell products straight to consumers, digital-physical brand strategy means updating a sponsorship model for the platform economy or directly imitating platforms themselves.

Traditional sponsorship continues to be a “platform” in a metaphorical sense. Brands still pay to put their names on various forms of culture and support the industries involved. But in the context of the gig economy, businesses and digital platforms are also aiming to more literally control the venues, processes, and formats attached to creative work — what sociologists would call the “means of cultural production.”

Digital platforms have been successful at cultivating user bases that subsequently yield distinct subcultures and audiences. Vloggers are on YouTube, celebrities and photographers are on Instagram, alternative musicians are on Soundcloud, and so on. The same logic has a spatial analogue in the incubator, where freelance workers are part of a proprietary physical and social space associated with a brand name.

Incubators like Red Bull Studios in Chelsea and MINI’s A/D/O in Greenpoint instrumentalize the cultural fetish around creative industries by “onboarding” groups of precarious cultural practitioners like musicians and designers.12 Red Bull Studios’ state-of-the-art recording facilities and built-in promotion machine, for example, are invaluable to emerging musicians, whose recordings and image in turn feed Red Bull’s well-calibrated content marketing campaigns.13

A/D/O, a ‘design, retail and creative work hub’ operated by MINI, opened in Greenpoint, Brooklyn at the beginning of 2017.

A/D/O, a ‘design, retail and creative work hub’ operated by MINI, opened in Greenpoint, Brooklyn at the beginning of 2017.

Although an incubator is an off-the-shelf strategy by now, brands have to achieve at least the perception of genuine symbiosis to be successful. Red Bull Studios works because it is so closely enmeshed with different music scenes, granting exposure and creative control in return for curatorship and buy-in from within the creative community.14

Similarly, A/D/O aims for a sophisticated demographic by finding partners like the Architectural League of New York and cutting-edge design studios to fill out its billing as a hub for design practice in New York City. Non-profit incubators like the New Museum’s New INC (where Consortia is located) are also designed to plug into freelance creative economies, and are available to brands as temporary sources of talent, strategic intelligence, and cultural partnerships. These relationships highlight the reality of an urban cultural landscape rooted in new kinds of public-private cultural partnerships, where the literal space of creative practice is a valuable layer in the “stack” of any forward-looking marketing strategy.

Spectacles of Culture

A third species of branded space attempts to build the brand into a proprietary cultural universe populated by visitors. It blends elements of the post-digital lifestyle space with the type of spectacle typically associated with the grand exhibitions and World’s Fairs of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Not unlike the immersive IBM and General Motors pavilions designed by modernist architects like Charles and Ray Eames and Norman Bel Geddes for Expo ‘64, theses spaces invite the public to experience a new cultural milieu as presented through the expertise of the brand itself.15

Samsung’s massive 837 space in the Meatpacking District is an example of this kitchen-sink approach to showcasing the future. The five-story showroom-cum-exhibition hall shuffles interactive installations, DJ booths, an upscale café a screening room in between Ikea-style product dioramas and Genius bar service desks. Landing in the middle of today’s Disney-fied Meatpacking District, 837 successfully draws handfuls of its target audience by enacting the right ways to experience culture through technology: watch TV like so, install your appliances with these accessories, drink cold brew while scrolling, and look out for more selfie-ops in the Samsung installation art space.

These spaces connect with broad audiences by posing the brand as a welcome mediating presence in contemporary culture. In a world of mass curatorship, they are the physical analogue to Spotify’s sponsored playlists or LVMH’s de-branded online magazine NOWNESS. Like both of those models, they are also free.

Take the new “Cadillac House” in the West Village, a combined showroom and lifestyle space “curated” by Visionaire Magazine that features a public lounge, a café, an art gallery, and multimedia displays that blend advertising with art.16 It may be hard to understand why anyone would sip a cortado right next to a new car, but the space offers an open venue for members of the creative economy clustered nearby to relax and attend events plugged into their professional world.

Cadillac House, designed by Gensler, aims to engage with culture in a substantive way while still prominently showcasing Cadillac products.

Cadillac House, designed by Gensler, aims to engage with culture in a substantive way while still prominently showcasing Cadillac products.

It also offers a default space for hosting the concatenated partnerships between magazines, artists, fashion labels, tech companies, and other players with their own goals and audiences. Whether they are experiential strategies sponsored by large corporations or independent networks of upscale co-working spaces like WeWork, NeueHouse, Soho House, or Camp David, such venues for the social layer of cultural industry are becoming increasingly important as branding opportunities.

The ways that brands manipulate architectural space speak to the way they view their customers, and the way their customers see themselves relating to culture, technology, and existing platforms for expression. Even if they don’t throw terms like “retail concept” around in casual conversation, most people are attuned to the types of advertising, design, events, and social content that constitute the economy of aspirational branding in the city.

These are realities that bear much deeper exploration at a moment of extreme gentrification and sliding affordability, when independent creative projects rely on a shrinking network of non-profit institutions and public space is policed and surveilled to the advantage of corporate property-owners. As the line between physical and digital experiences blurs, and people content with the limitations and opportunities of proprietary platforms, citizens and brands will have to renegotiate the rights and privileges implicit in the spaces of the city.

-

Omni-Channel Shoppers: An Emerging Retail Reality

-

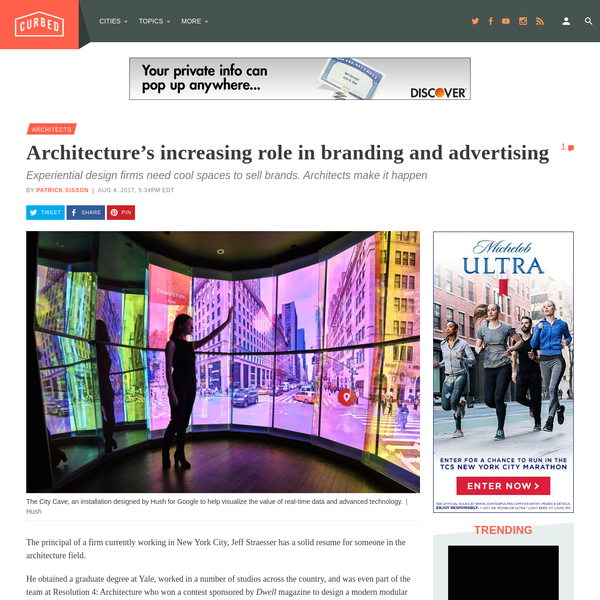

Architecture's increasing role in branding and advertising

-

Excerpt: Identity Theory in a Digital Age

-

Warby Parker, Bonobos Have Big Plans for Physical Stores

-

Everlane Soho Studio

-

Warby Parker Retail

-

Southdale Center: America's first shopping mall - a history of cities in 50 buildings, day 30

-

Saturdays Surf NYC

-

0208_rfcafe_slide_1.jpg

-

An 18-Year-Old Instagram Star Says Her "Perfect Life" Was Actually Making Her Miserable

-

AIRSPACE

-

Eric-by-the-sea on Twitter

-

A/D/O | Home

-

Red Bull Studios New York

-

Stephen O'Malley | Red Bull Music Academy

-

1964: The New York World's Fair